Benchmarks

Particle filtering

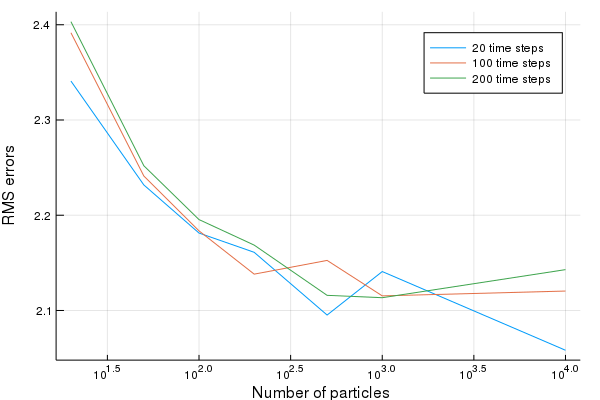

To see how the performance varies with the number of particles, we simulate several times. The following code simulates the system and performs filtering using the simulated measurements. We do this for varying number of time steps and varying number of particles.

function run_test()

particle_count = [10, 20, 50, 100, 200, 500, 1000]

time_steps = [20, 100, 200]

RMSE = zeros(length(particle_count),length(time_steps)) # Store the RMS errors

propagated_particles = 0

t = @elapsed for (Ti,T) = enumerate(time_steps)

for (Ni,N) = enumerate(particle_count)

montecarlo_runs = 2*maximum(particle_count)*maximum(time_steps) ÷ T ÷ N

E = sum(1:montecarlo_runs) do mc_run

pf = ParticleFilter(N, dynamics, measurement, df, dg, d0) # Create filter

u = @SVector randn(2)

x = SVector{2,Float64}(rand(rng, d0))

y = SVector{2,Float64}(sample_measurement(pf,x,u,0,1))

error = 0.0

@inbounds for t = 1:T-1

pf(u, y) # Update the particle filter

x = dynamics(x,u,t) + SVector{2,Float64}(rand(rng, df)) # Simulate the true dynamics and add some noise

y = SVector{2,Float64}(sample_measurement(pf,x,u,0,t)) # Simulate a measuerment

u = @SVector randn(2) # draw a random control input

error += sum(abs2,x-weighted_mean(pf))

end # t

√(error/T)

end # MC

RMSE[Ni,Ti] = E/montecarlo_runs

propagated_particles += montecarlo_runs*N*T

@show N

end # N

@show T

end # T

println("Propagated $propagated_particles particles in $t seconds for an average of $(propagated_particles/t/1000) particles per millisecond")

return RMSE

end

@time RMSE = run_test()Propagated 8400000 particles in 1.140468043 seconds for an average of 7365.397085484139 particles per millisecond

We then plot the results

time_steps = [20, 100, 200]

particle_count = [10, 20, 50, 100, 200, 500, 1000]

nT = length(time_steps)

leg = reshape(["$(time_steps[i]) time steps" for i = 1:nT], 1,:)

plot(particle_count,RMSE,xscale=:log10, ylabel="RMS errors", xlabel=" Number of particles", lab=leg)

Comparison against filterpy

filterpy is a popular Python library for state estimation. Below, we compare performance on their UKF example, but we use a longer trajectory of 50k time steps:

Python implementation

from filterpy import *

from filterpy.kalman import *

import numpy as np

from numpy.random import randn

from filterpy.common import Q_discrete_white_noise

import time

def fx(x, dt):

# state transition function - predict next state based

# on constant velocity model x = vt + x_0

F = np.array([[1, dt, 0, 0],

[0, 1, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 1, dt],

[0, 0, 0, 1]], dtype=float)

return np.dot(F, x)

def hx(x):

# measurement function - convert state into a measurement

# where measurements are [x_pos, y_pos]

return np.array([x[0], x[2]])

dt = 0.1

# create sigma points to use in the filter. This is standard for Gaussian processes

points = MerweScaledSigmaPoints(4, alpha=.1, beta=2., kappa=-1)

kf = UnscentedKalmanFilter(dim_x=4, dim_z=2, dt=dt, fx=fx, hx=hx, points=points)

kf.x = np.array([-1., 1., -1., 1]) # initial state

kf.P *= 0.2 # initial uncertainty

z_std = 0.1

kf.R = np.diag([z_std**2, z_std**2]) # 1 standard

kf.Q = Q_discrete_white_noise(dim=2, dt=dt, var=0.01**2, block_size=2)

zs = [[i+randn()*z_std, i+randn()*z_std] for i in range(50000)] # measurements

start_time = time.time()

for z in zs:

kf.predict()

kf.update(z)

# print(kf.x, 'log-likelihood', kf.log_likelihood)

end_time = time.time()

print(f"Execution time: {end_time - start_time} seconds")Execution time: 6.390492916107178 secondsJulia implementation

using LowLevelParticleFilters, StaticArrays, LinearAlgebra, BenchmarkTools

const dt = 0.1

function fx(x,u,p,t)

# state transition function - predict next state based

# on constant velocity model x = vt + x_0

F = SA[1.0 dt 0.0 0.0;

0.0 1.0 0.0 0.0;

0.0 0.0 1.0 dt;

0.0 0.0 0.0 1.0]

return F*x

end

function hx(x,u,p,t)

# measurement function - convert state into a measurement

# where measurements are [x_pos, y_pos]

return x[SA[1,3]]

end

x0 = SA[-1.0, 1.0, -1.0, 1.0] # initial state

R0 = 0.2I(4) # initial uncertainty

z_std = 0.1

R1 = LowLevelParticleFilters.double_integrator_covariance(dt, 0.01^2)

R1 = SMatrix{4,4}(cat(R1, R1, dims=(1,2))) # Called Q in the Python code

R2 = Diagonal(SA[z_std^2, z_std^2]) # Called R in the Python code

d0 = LowLevelParticleFilters.SimpleMvNormal(x0, R0)

ukf = UnscentedKalmanFilter(fx, hx, R1, R2, d0; nu=0, ny=2, Ts=dt, p=nothing)

zs = [[i+randn()*z_std, i+randn()*z_std] for i in 1:50000] # measurements

function runsim(ukf, zs)

for z in zs

predict!(ukf, SA[])

ll, _ = correct!(ukf, SA[], z)

# @show ll

end

end

runsim(ukf, zs)

time_julia = @belapsed runsim($ukf, $zs)0.017676814Result

time_python = 6.390492916107178

time_python / time_julia361.51836615507625The Julia version is about 360x faster than the Python version.